A Recipe for Successful Teams

Associations Now

Associations Now

Chef Jeff Henderson's unusual life path has taken him from drug dealing to prison to haute cuisine. Along the way, he's learned plenty about what makes good food and great teams. For both, the right mix of ingredients is essential.

Jeff Henderson begins his 2007 memoir, Cooked, with a story about a job interview. As opening scenes go, that doesn’t sound especially stirring. But Henderson was, and is, an unusual case. In 2000, he was an ex-felon aiming for a job as a high-profile chef at Las Vegas’ Caesars Palace and was well aware of all the reasons many prospective employers might immediately pass on him: He was a black man, raised in poverty, not long out of prison.

So Henderson did what too few job candidates—and, often, too few leaders—do. He studied up on the culture at the workplace. He chatted up the kitchen staff as they arrived for their shifts. He learned what kind of food the executive chef liked and found out how it was prepared. He quizzed hostesses on the workplace vibe. He learned how the kitchen worked, up and down the ladder.

“By the time I walked into the man’s office,” he writes, “I was comfortable, confident.”

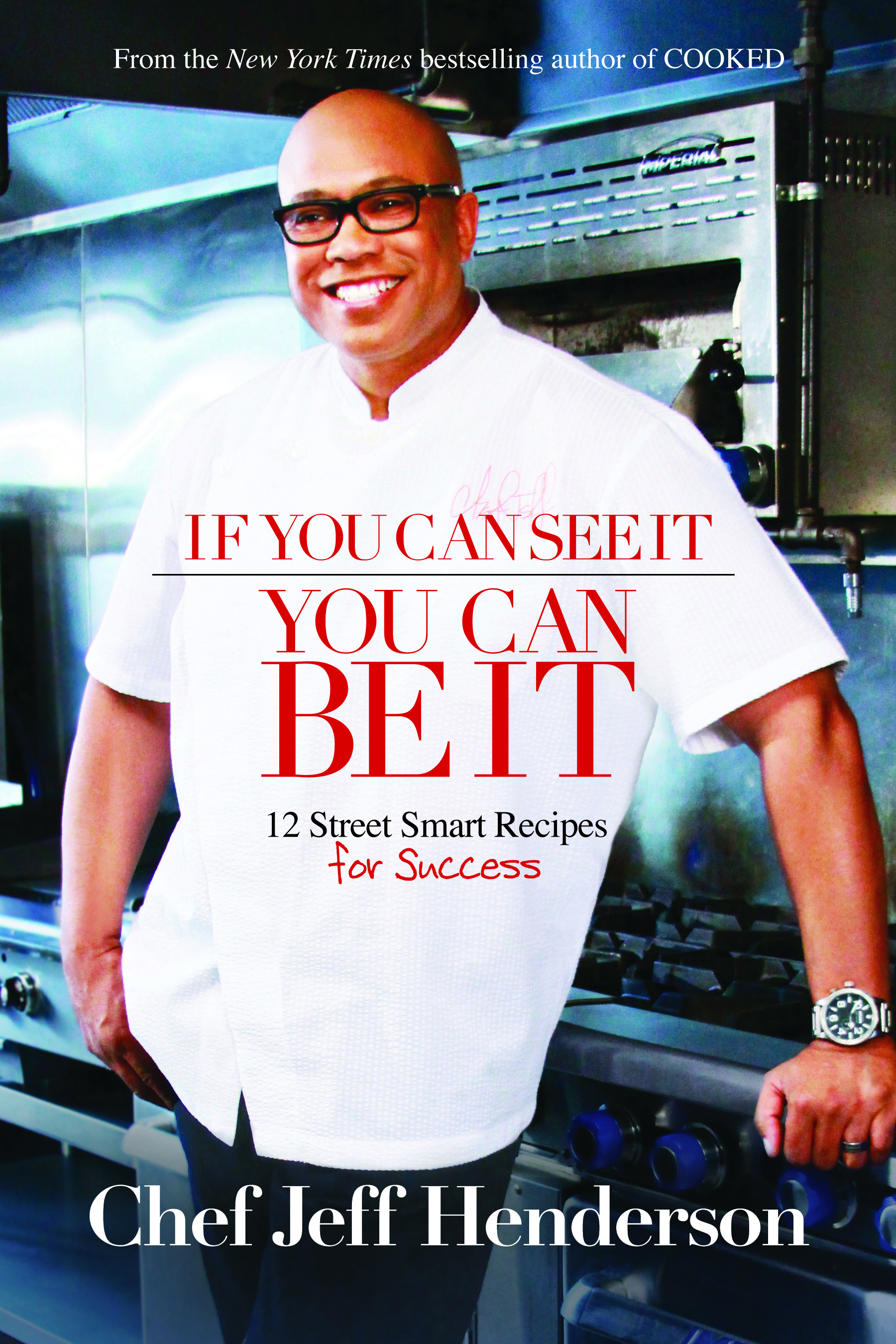

Henderson, the closing keynote speaker at the 2017 ASAE Annual Meeting & Exposition in Toronto this summer, has parlayed that savvy not only into the job at Caesars but also into a pioneering career in cuisine and media. He became the first African-American executive chef at the Bellagio Hotel, wrote two more books, and today hosts the nationally syndicated cooking show Flip Your Food. In conversation, though, he’s a spirited advocate for improving workplace cultures and getting leaders to do more than pay lip service to diversity and inclusion.

“I believe diversity is the key to any successful business, especially in America,” he says. “America is a gumbo with multiple ingredients. So when your organization reflects every culture, every religious background, every different type of education, it becomes attractive all the way across the board.”

You’ve heard that before, sure. But Henderson came by that lesson in an unusual way, and he says he’s certain we still don’t teach it right.

Kitchen Prep

Henderson is careful when he talks about how he learned about leadership. Selling drugs, as he did in Southern California before his decade-long prison sentence, is not the same thing as getting an MBA. That time was a “dark moment,” he says. He doesn’t want to glamorize it. But he also recognizes that he was effectively running a highly profitable business—generating $35,000 a week, by his estimate—and that he couldn’t have managed it without solid business skills.

“Any person who sells a product, you have a team of people,” he says. “You manage that team. You look for creative ways to corner the market, you look for creative ways to recruit the right talent for whatever position is available. And then the number-one goal with any organization is retention: How do you retain great people who work for you?”

So when Henderson was put on kitchen duty in prison, he treated it as another new business to learn and master. He worked extra shifts, avoided breaks, tried to learn everything he could about cooking from those around him. Upon his release, he hustled his way from line-cook and dishwasher gigs in Los Angeles to bigger responsibilities in Las Vegas.

Henderson argues that prison was valuable, not just for stoking his love of cooking and his work ethic, but for preparing him for the high-end cooking world by introducing him to a cross-section of society—all felons, to be sure, but from a variety of cultural backgrounds.

“I became culturally intelligent in prison,” he says. “The first time I ever sat at a table and ate with a white guy in my life was in prison. The first African I met in my life was in prison. The first Jewish guy, the first Muslim.

“I grew up in an exclusive black community, and as I began to build relationships with this diverse population of incarcerated men, I began to respect and understand the thinking process of these people.”

Cultural Intelligence for Organizations

Henderson thinks a lot about cultural intelligence, because he tries to employ it in his own business—and he thinks few organizations do it enough in theirs. Most organizations recognize the value of diverse workforces, and they likely have CEOs who deliver that message, along with rank-and-file staffers from diverse backgrounds. But, Henderson notes, many managers are poorly trained in how to lead those teams and understand that vision.

“Middle managers need to be trained and taught the history of the various subcultures of the people they manage and potentially hire,” he says. “Most people judge various races and cultures based on the media: If you hire a black man, and he’s dark skinned, and he has a beard, he has potential to be violent, or maybe he’s been to prison, or blah, blah, blah. You can’t play into those stereotypes.”

So how do you train managers to avoid that? Henderson’s pie-in-the sky idea is that they should spend a month living in the communities their employees live in. Barring that, they can recognize that there is plenty of difference within ethnicities and that good staff management involves recognizing class distinctions.

“I would bring in three people from one ethnic background: an African-American person from inner-city America, from poverty; an African-American person who has middle-class values from suburbia; and a highly educated African American,” he says. “Then present a panel, and then begin to have conversations about these individuals’ life experiences.”

Henderson adds that motivated and well-educated people who come from poorer backgrounds still have particular needs unique to their upbringings.

“One thing that people from that experience lack is they never got praised growing up,” he says. “So I am a big patter-on-the-back [with them], I’m a big praiser: ‘Oh my God, that is a great omelet you just made, but let me tell you how I can help you make it better. If you just add a little more salt and a little more pepper, now you’ve got an amazing, superstar, magazine omelet.’ And that person says, ‘Oh, wow, really, Chef? You really like it?’”

Teachable Teams

Just as many managers need to shrug off their stereotypical assumptions about different kinds of employees, workers ought to be encouraged to understand an organization’s culture, Henderson points out. A busy kitchen (or association) is a team, and there’s no room for know-it-alls who see certain tasks as below their pay grade.

“What I look for in an employee coming in is someone who is teachable,” he says. “Someone who is willing to learn and doesn’t come in with that mindset of, ‘I know everything, I have a college degree.’”

Henderson himself says he still has work of his own to do. Cooking he’s great at, and he’s not too shabby at brand management either. But he says he wants to understand finance better, and he’s also learning how to swing for the fences more when it comes to his ambitions. His charitable work targets mass incarceration and eradicating poverty, an outsize goal that involves “teaching the hidden rules of the middle class to the folks who come from poverty so they have a better chance of obtaining employment and education.”

“I met my wife when I was incarcerated, and I sold her on my dream when I was in prison. I said I want to become a chef, and I want to pay it forward and give back to communities around this country. And that’s what I’ve been doing for the past 20 years,” he says.

“I think this is really a natural evolution of me and what I’m doing today,” Henderson adds, then laughs at how far he is from his youth and, sometimes, even from the kitchen. “My wife always says, ‘Honey, no one’s calling you to cook.’”

[This article was originally published in the Associations Now print edition, titled "America Is a Gumbo."]

A Personal Rebrand

Jeff Henderson worked to reinvent himself on his way to a new life after prison. It meant taking a hard look at how people would perceive him and what steps he could take to change those notions. Here’s a brief exchange on that subject from his interview with Associations Now:

You’ve talked about how, because you had a past as a felon, you had to work a lot harder at networking and relationship building. How did you cultivate those skills?

I had to be a chameleon. I had to make sure the prison stigma, the street stigma, the drug-dealer stigma disappeared. I had to rebrand myself, changing the way I walk, the way I talk. I had to clean-shave my face. I had to take a portrait of a black man in America who had no formal education and who’d been to prison and create an image acceptable in corporate America. I also needed insider information. I needed to have a relationship on the inside so I could have someone pull that resume. Everything I had to do was unorthodox, in order to get in.

What was the hardest part of that transformation?

Learning middle-class values. I had to understand the hidden rules of the middle class. I learned early on that people judge you by the cover of the book. People judge you by the color of your skin. People judge you by the clothes you wear, how you dress, how you eat. What you order on the menu tells your story when you’re out with middle-class clients. So I had to understand how middle-class people think, from the cars they drive, the type of shoes, the socks, their vocabulary. I had to pretty much rebuild myself.